|

Zooming into the Past |

|

Dr. Gacaliye Hints of Regional Confederation Introduction To begin with, there is the question of why the Roobdoon Forum lays so much emphasis now on late ambassador Mohamed Said Samantar’s interview with the French quarterly review journal, Afrique Contemporaine. The simple answer is: the Forum devotes so much of its review to materials that deemed to the Forum as a milestone to the contemporary history of Somalia. In this interview, diplomat Samantar treats numerous complex and controversial issues, from Somali nationalism to political confederation of the Horn of Africa. Mohamed Said Samantar (Gacaliye), who fell out with President Siyaad Barre in early 1980s, articulates his own account of Somali polity. His responses are meticulous and detailed analysis of Somali’s recent history. For him, the Somali unity was/and still is being undermined by the divisive rivalry between Somali elites whom he classifies one group as Italianized Somali intellectual class. In Somali politics, it is often underrated this notion of Second-language syndrome, whereby ESL/ISL became the differentiating mark of the Somalis. Can we say that the Italian-speaking Somali elites of the 1960s did try, as Samantar argues, to make Somalia an Italian-speaking country and, in the process, failed Somalia to become a united Somali-speaking country? In other words, is this Anglophone/Italophone elitism mark what appears to be an already unfolding Somali problem between the North and the South? While the principles of Somali elites of the 1960s were Somali nationalism, Samantar’s account suggests that the Italian-educated leadership were under pressure to vigorously tow the Italian government line. Probably, this line of making Somalia an Italophone seems to be cherished by few southern elites who were only concerned in their careers. Safe-guarding the link with Italy, therefore, became their priority, compromising any dose of Realpolitik that could accelerate the unification of the Somali-speaking people in the Horn of Africa. It could as well be the cost of retaining this Somali-Italian link that resulted in the image of the present Somali situation. Somali elites of the 1960s wished to have their cake and eat it too with regard to Somali unity. The cost of retaining the illusory of Italian-speaking country for too long paved the way for many concerned Somali politicians to re-think another geopolitical approach to unite the dispersed Somalis in the region. In this interview, Ambassador Samantar expresses his feelings, imagining a political confederation of Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea. Samantar also discusses the events that led to the 1969 Revolution, stating that Prime Minister Egal’s renunciation of “Somali people's right to self-determination” was the genesis of the military take over. He also traces the devastating policies adopted by Siyaad Barre, both domestic and international affairs. At this point, the Forum presents to its readership the complete interview with the Ambassador by Ahmed Dehli of AFRIQUE CONTEMPORAINE.

Expatriate Opposition Leader on Historical Bases Paris AFRIQUE CONTEMPORAINE in French Vol. 154 No. 2, 1990 pp 54-59

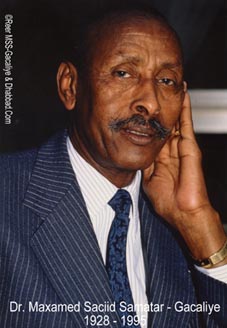

[Interview with opposition leader Mohamed Said Samantar [Gacaliye] by Ahmed Dehli, in Paris in March 1990; the first six paragraphs are AFRIQUE CONTEMPORAINE introduction; footnotes shown as published]. [Text] Mohamed Said Samantar was born in Wardheer in the Ogaden, [Ethiopia]. While very young, he participated in the fight for his country's independence. In 1949 he joined the Somali Youth League, a movement opposing the British occupation. After attending normal school, he became an elementary teacher, then worked for Radio Mogadishu and, in 1958, went to Rome, where he was placed in charge of RAI (Italian Radio Broadcasting and Television Company) broadcasts to Africa. While in Rome, he studied political science at the university level. In 1960, M.S. Samantar joined the Somali Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He was ambassador to the European Economic Community in Brussels from 1963 to 1966, to Italy and the FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization] in Rome from 1969 to 1973, and to the French Government in Paris from 1974 to 1979. He was appointed minister of state at the presidency in Mogadishu in 1979 and placed in charge of relations with the Western powers in a particularly touchy regional and international context involving the commitment of the USSR and Cuba on behalf of Ethiopia. In 1980, M.S. Samantar headed the Somali delegation visiting Washington to discuss an agreement with the United States. The agreement as signed was unfavorable to Somalia, and that fact led the fervent nationalist to resign from Siyaad Barre's government. His resignation took effect in 1982. Since that time, M.S. Samantar has lived in Paris, where he campaigns for coordination of the various movements opposing the Mogadishu government. In this interview, which took place in March 1990, Mohamed Said Samantar explains the problems currently facing Somalia and discusses the prospects for change that might help solve those problems. [Dehli] Can you refresh our memories concerning the conditions surrounding the birth of Somali national feeling? [Samantar] Somali national feeling arose during the bitter struggles that the Somali have carried on against various colonialist forces since the 14th century. But it was in 1888 that our nationalism really came into being. That was when the entire people rose up to confront British, Italian, and French troops. The country's ancient and recent history consists in fact of a struggle against every kind of domination: Arab, Persian, European, and so on. [Dehli] Considering that Somalia has no mineral resources, why is it still important geopolitically? [Samantar] Somalia does not have mineral wealth, but it occupies a geopolitical position between the Bab al-Mandab, the Gulf of Aden, and the Indian Ocean (see the following map) that is very sensitive as far as both the West and the East are concerned. That was why the country was divided up by the British, French, and Italians in 1896. Today, destabilization is continuing within the particularly touchy context of the Horn of Africa. [Dehli] Some sociologists say that Somalia's current situation is explained by the fact that each clan group is struggling to safeguard its own distinctive features. [Samantar] I defy anyone to prove scientifically that there is any socio-cultural diversity whatever among the various families making up Somali society. Permit me to add that Somalia is the only African nation consisting of a single ethnic group speaking a single language. Even during the colonial period, when people talked about British, French, or Italian Somaliland, the ethno-cultural unity was very real. It was even used to surmount the many internal and external barriers and to face up to the various local and international challenges. [Dehli] You have just told us that Somalia as an African nation has its own specific nature. So why did it join the Arab League in 1974? [Samantar] For centuries and centuries, we have had close cultural, economic, and spiritual ties to the Arabian Peninsula. It was in the 13th century that our ties to the rest of the Arab world were strengthened. In the years following independence (1960), Somalia tried to overcome a degree of isolation. [Dehli] Some African countries have had trouble accepting your membership in the Arab League. How do you account for that fact? [Samantar] The destiny of an independent country and the future of a sovereign people are never determined by the reactions of other countries. Being jealously attached to our African character, we are Somali first of all and then members of the Arab League. [Dehli] Do you think that the Arab governments will be content with your membership in their league and that they will not try to carry out very rapidly a policy for the Arabization of Somalia to the detriment of its historical and cultural identity? [Samantar) You are completely right to ask that question. I would like to tell you that by deciding in 1972 to transcribe our language using the Roman alphabet, we were already taking a not insignificant step toward protecting ourselves from that attempt at Arabization. This problem will certainly arise in the near future. At any rate, if the Arab world ever tried to make us submit to its policy, Somalia would turn its back on the Arab League for good. [Dehli] Can you tell us why? [Samantar] Under no circumstances would I want to replace my Somali national identity with an Arab or any other identity. Incidentally, certain Somali writers have sensed the danger and expressed their hostility to Arabization, sometimes in terms that are a little hard on the Arabs. [Dehli] If you don't mind, let us go on to Somalia's internal problems. General Mohamed Siyaad Barre celebrated the 20th anniversary of his accession to power on 21 October 1989. What is the result of those 20 years of unshared power? [Samantar] Very often in Africa, those rebelling against a government will heap blame on it for anything and everything at the risk of creating total confusion between political discourse and the daily reality being experienced by the population. That is why I will tell you that in October 1969, there was a radical political change in Somalia as a result of the assumption of power by the Somali Armed Forces, which were the symbol of national pride and the only hope the Somalis had for getting out of the impasse they were in. From 1969 to 1976, just before the establishment of the single party the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), which is Marxist-Leninist – the country experienced tremendous progress in all areas – so much so that Somalia had become self-sufficient in every respect and the Somali experience was being pointed to as a model in Third World countries. I remember that several observers and researchers came from the African continent, Latin America, and even Portugal to study our political experience, which was characterized by, among other things, a literacy campaign, a volunteer service, equality between men and women, the near elimination of corruption and the clan spirit, and so on. [Dehli] Would you explain to us the reasons behind the political change that occurred in Somalia in October 1969? [Samantar] To better understand the politico-historical context in which the coup d'etat of 1969 took place, we must take a quick look back at history. Great Britain had promised the Somali Government in 1961 that it would grant the right of self-determination to the Somali living in the Somalia Northern Frontier District [SNFD], provided that Somalia rejoined the Commonwealth. But at the time, Italian Prime Minister Antonio Segni, Somali President Adam Abadalla Osman, and the Italianized Somali intellectual class were doing everything they could to keep Somalia an Italian-speaking country. That was why the 1963 conference in Rome between Kenya and Somalia, with the participation of Italy and Great Britain, for the purpose of deciding the future of the SNFD ended in failure. Two weeks later, the minister of British colonies, Duncan Sandys, declared unilaterally that effective on a given date, the SNFD would be Kenya's seventh province despite the will of the local inhabitants, who, during the referendum held in 1962 under the auspices of British, Nigerian, and Canadian jurists, had voted by a near majority [as published] (86.7 percent) to join Somalia. In 1967, during the Arusha conference in Tanzania, which was attended by Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda, Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta, and Somali Prime Minister Mohamed Ibrahim Igal, the Somali head of government renounced – for the first time in the country's history the Somali people's right to self-determination. That act, which was felt to be a historic betrayal, was at the origin of the military coup d'etat of October 1969. [Dehli] What have been the most significant changes in the country since the establishment of the SRSP under General Barre's leadership? [Samantar] As a result of the establishment of that single party, which has become the absolute master of the situation, the country is governed by a Supreme Revolutionary Council consisting of 19 individuals under the chairmanship of M.S. Barre. That was what brought Somalia into an era of dirigisme and bureaucracy. [Dehli] Was there a need to establish the SRSP? [Samantar] None whatever. Moreover, that single party is regarded by the Somalis as a deviation from the national program adopted in October 1969 [3] and a major factor in the country's destabilization. That political party was not a product of Somalia's historical, political, and socio-cultural reality. On the contrary, it was the Soviet Union that took advantage of President Barre's weakness to force upon him the idea of establishing a Marxist-Leninist party at the top of the Somali state, something which the majority of the population rejects. [Dehli] Why did the Soviets want to impose a Marxist-Leninist party on the Somali state's leadership? [Samantar] From the Soviet Union's standpoint, establishing that party provided an additional guarantee that Somalia would remain within its sphere of influence. [Dehli] How do you explain the rupture between Moscow and Mogadishu that took place a year after the party was founded? [Samantar] When the war in the Ogaden broke out between Ethiopia and Somalia in 1977, the Soviet Union supported the military regime of Colonel Mengistu Haile-Mariam despite the many coordination and friendship agreements and conventions that Nicolay Podgorny, chairman of the President of the Supreme Soviet, had signed with Somali President M.S. Barre in Mogadishu on 24 July 1974. In that crucial period in the history of the Somali nation, the SRSP burned all the bridges linking it with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. [Dehli] What is your analysis of Soviet policy on the Horn of Africa during that period? [Samantar] The Soviet Union's big concern was to control Somalia, Ethiopia, and South Yemen with a view to imposing its supremacy both in the Red Sea and in the Indian Ocean. [Dehli] After breaking off diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, why did the Somali president insist so strongly on safeguarding a party that had been forced on him to start with? [Samantar] Because President Barre had no legitimacy outside the party. [Dehli] In 1980, you headed the delegation that signed an agreement with the United States in Washington. Can you explain to us the nature of that agreement, which is still in effect? [Samantar] Somalia grants certain military facilities to the Americans in Mogadishu and in the port of Berbera. As for the Americans, they are committed to helping Somalia militarily and materially, but the U.S. Administration has not lived up to its commitments [4]; that is why I see no value in keeping that agreement in effect. [Dehli] Did your resignation from the Somali Government on 6 September 1980 have anything to do with that stand? [Samantar] I decided to resign for three important reasons: the president of the republic and the people around him did not listen to me in 1977, when I advised them not to accept aid from the Arab countries (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and countries on the Gulf) because of my strong conviction that the offer from those countries was calculated to help them strangle us more completely later; and, instead of supporting the Western Somalia Liberation Front (WSLF) [5], the Somali Government tried hard to gain control of it without considering the unfortunate reactions that would result. The fact is that since neither the Somali nor the WSLF leadership and rank and file had accepted Mogadishu's interventionist policy – it was regarded as intolerable interference in Ethiopia's internal affairs by almost all African countries – I could not tolerate my country's signing of a dishonest and humiliating agreement with the United States in Washington on 22 August 1980. [Dehli] What do you think of the peace agreement signed on 4 April 1988 by the Ethiopian Mengistu Haile Mariam and the Somali M.S. Barre following the 1977 war between the two countries? [Samantar] It was more a fool's bargain than a genuine peace agreement between the two peoples. Colonel Mengistu is finding it very hard to cope with the many problems currently being experienced in Ethiopia [6]: the wars being waged in Eritrea, Tigre, Western Somalia, and the Oromo and Afar regions by the various national movements demanding that the central government in Addis Ababa recognize their national dignity; the increasingly strong influence of the other political parties; and the profound unrest, which is slowly but surely taking hold in the military apparatus and weakening the political power in Ethiopia just a little more. The Ethiopian president therefore needed to sign that peace agreement with Somalia so he could move his military divisions from their positions on the Ogaden front to the fronts in Eritrea and Tigre. As for the Somali president, he was being hampered not only by several difficulties of a political, economic, and social nature but also by the persistence of the civil war that has been raging over the country for the past 11 years. Gen. Barre therefore felt the need to sign an agreement with Col. Mengistu so he could announce a political success to the Somalis without worrying about the trap set by Ethiopian diplomacy. [Dehli] Would you explain to us the basic clauses in that agreement dated 4 April 1988? [Samantar] That agreement provides for: · An immediate cease-fire with a view to ending the war. The withdrawal of both armies from the border. The exchange of prisoners of war. · The restoration of diplomatic relations. Good-neighbor relations based on mutual respect and noninterference in the internal affairs of the other country. [Dehli] Since you consider that agreement to be a “fool’s bargain,” how would you envision the solution to the Ogaden problem? [Samantar] Before answering, I want to point out to you that despite the agreement signed by the two parties, the Ogaden issue remains unresolved because the two chiefs of state were very careful not to tackle that thorny problem. On 8 April 1988 – that is, only four days after the agreement in question was signed – I drew up a six-point statement of my views on how to settle the Ogaden issue – which has been poisoning relations between Somalia and Ethiopia for a very long time – once and for all. It is necessary to: · Demilitarize the region, completely. · Grant the people of the Ogaden regional autonomy for five years. · Help the Ogaden recover both economically and culturally with the help of the Ethiopian and Somali Governments. · Prepare the inhabitants to exercise their right to self-determination with the participation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and the United Nations (UN). Hold a referendum under UN auspices to allow the people of the Ogaden to freely choose their political future: the establishment of an independent state, union with Ethiopia, or a return to Somalia. · Last, obtain a formal commitment from Ethiopia and Somalia that they will respect the choice made by the Ogaden's people. [Dehli] To get back to the internal problems that have been shaking Somalia for about three years, does President Barre still rely on the support of the Marehan clan, to which he belongs, to remain in power? [Samantar] Absolutely not. Proof of this is that on 26 May 1989, intellectuals, members of Parliament, company managers, and military men – all belonging to the Marehan group – placed in his own hands a letter in which they asked the chief of state to: · Make a statement on radio and television acknowledging the failure of his policy and his inability to find a solution to the civil war that is exhausting Somalia and the Somali. · Appoint a prime minister to form a provisional government with the mission of preparing for the holding of free elections in the country within six months. · Revise the Constitution with a view to establishing a political system based on plurality of opinion and granting freedom of the press, freedom of expression, and freedom to demonstrate. · Set up a program capable of bringing the country out of its apathy and stagnation and starting the economy out on the path to liberalism. · Rebuild the northern part of the country, which has been seriously jeopardized by the civil war. · Hold an early, free, and fair presidential election that will allow the nation's great political figures to run without necessarily being members of the party. [Dehli] Why did it take the Somali prime minister, General Mohamed Ali Samantar, almost a month and a half to put together the government that was formed on 15 February 1990? [Samantar] Relations between the chief of state and the prime minister had deteriorated. The president wanted his sons and cousins to be part of the new government, but the head of the government would not agree to assign portfolios to individuals not acceptable to Somali public opinion. In that tense political climate, the makeup of the government became a real headache. Mohamed Ali Samantar represents in fact the last card that President Barre can still play on either the national or the international level. That is why the Somali have nicknamed him “the fireman.” Every time a political “fire” breaks out somewhere, the president calls on him to put it out, but how long will that continue? [Dehli] How do you explain the relative calm that Somalia experienced – paradoxically – during the absence of a government, not only in the north, where the Somali National Movement (SNM) is increasingly active, but also in the center, where the members of the Somali National Congress (SNC) are concentrated, and in the south, where the Somali Patriotic Front (SPF) sporadically attacks government garrisons? [Samantar] All the fronts except the SNM have exhausted their resources and are incapable of destabilizing the government. As for the effective presence of the SNM, that is explained by the fact that that movement is playing the anti-Somali card and benefiting from the aid that Somalia's enemies are bestowing on it so generously. [Dehli] In reality, are there internal factors justifying the appearance and continued existence of the SNM? [Samantar] The disastrous policy adopted by President M.S. Barre since the founding of the SRSP in 1976 has brought the country to the verge of political and economic bankruptcy, and that fact has contributed to the emergence of several armed opposition movements, notably the SNM. M.S. Barre's regime must accept its full responsibility for the country's present situation, which is not an easy one. To answer your question about the relative calm prevailing in Mogadishu, I would simply like to say that the president of the republic promised the nation that he would carry out fundamental changes in all areas. As a result, no one tried to hamper his action or to make an already precarious situation worse. But both sides are deluding themselves, because the chief of state is no longer in a position to satisfy the Somali people by implementing the radical changes to which they aspire. That being the case, the political fight that will soon begin should seriously jeopardize the position of Gen. Barre and his team. [Dehli] Are the Somali Armed Forces still loyal to President Barre? [Samantar] If we exclude the few officers belonging to the president's family, we can flatly state that the Somali Armed Forces fully agree with the opposition felt by the rest of the population. [Dehli] So why aren't the Armed Forces stirring? [Samantar] It's only a question of time and opportunity. Moreover, it must not be forgotten that the president of the republic has entrusted all the key posts in the military apparatus to his sons and cousins. [Dehli] Has the famous political plan that might unite all the opposition movements in Somalia, and that has been so much talked about recently, finally been set up? [Samantar] For a long time we have been working patiently and passionately to put together a platform for uniting the various opposition fronts in the country and presenting a political force that will constitute a democratic alternative to Gen. Barre's dictatorial government. Except for the SNM, all the parties concerned have already expressed a favorable opinion of the plan, and we hope that the SNM will soon join us so that we can go into action. [Dehli] To conclude this interview, how do you think the situation in the Horn of Africa may develop? [Samantar] I feel that if a system of political confederation linking Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Eritrea were someday established on the basis of the right of peoples to self-determination, the Horn of Africa would be transformed into an oasis of peace, stability, and prosperity. If that happened, Somalia would rediscover its lost unity, Ethiopia would have access to both the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, Eritrea could freely choose its destiny, and Djibouti would find tranquility without being coveted by its big sisters. Peace could finally be established in that part of the African continent, and that is the sine qua non condition for its development, which alone will enable the inhabitants to view the future with optimism and hope. Footnotes [3] See the program in the documents following this article [not included]. [4] It is true that the United States did not help Somalia when the latter was attacked by Ethiopia and did not uphold the principle of the Ogaden's right to self-determination when that problem arose. [5] Established in 1966, the WSLF demands the right to self-determination for the Ogaden, a province that Great Britain ceded to Ethiopia in 1949. [6] See “Ethiopia: From the Junta to the Republic,” by Jacques Bureau, AFRIQUE CONTEMPORAINE, Vol. 147, No. 3, 1988, pp. 3-30, and “Eritrea,” an interview with Assayas Afwerki by Ahmed Dehli, AFRIQUE CONTEMPORAINE, Vol. 148, No. 4, 1988, pp. 49-55.

|